I almost wrecked the car on the return trip home from the doctor’s office. I was angry, disoriented, and grief-stricken. My wife and I had just finished up a third visit with the Developmental Pediatrician, a kind man who delivered devastating news about our two-year old son. Autism.

At the time of the diagnosis, my only reference point for Autism was the movie “Rain Man.” I imagined the adult version of my son – my first born – being completely dependent on a handful of adults. Gone were my dreams of Football Fridays, backpacking trips in the Appalachians, and greasy conversations under the hood of a pickup. I felt like fate or some other indiscriminate power had stepped into my “picket fence” family story and set off an explosion.

When we returned to the house, I kissed my son’s forehead, placed him in his bed for a nap, and then went out into the garage to vent. My wife would later acknowledge, “You were on a different planet that afternoon.” I screamed at first, before slinging boxes and tools across that cluttered, enclosed space.

A Changed Mind Changes Everything

At the height of my rage, I started to punch the small windows in the garage doors. Broken glass and blood splatters fell to the floor. While looking at my battered fist, I recognized that I had an important decision to make. I could keep feeling sorry for myself and my aspirational narrative of fatherhood, or I could pivot and support my family in a time of pressing struggle.

As I wrapped my hand in an oily rag, I started thinking about all the times I’d put my son on the back of my bicycle and led him to the little park at the center of our community. I thought about how he’d always insisted with grunts and the wave of an index finger that we needed to slide down the slide while visiting that special place. Strangely, I felt better.

With the opening barrage of the storm behind me, I realized that my son – my family – needed my support and action. Speech and physical therapy evaluations had to be scheduled. A behavioral analyst would need to be consulted. Calls to our insurance provider, local school district, and family members were among the many items populating the to-do list. We needed to get on the bike, too, and make our way to the park as we had done a million times before. It was a time for resilience.

What is Resilience?

If you ask a 100 people to define resilience, they will probably offer one hundred different definitions. “Resilience is toughness,” some might say, while others insist it’s “One’s readiness to take on trouble.” Often, a face comes to mine when we hear the word “resilience,” the face of a person we associate with overcoming significant troubles and pressing on with life. “Granny was resilient,” we might say, “she had a lot of grit.”

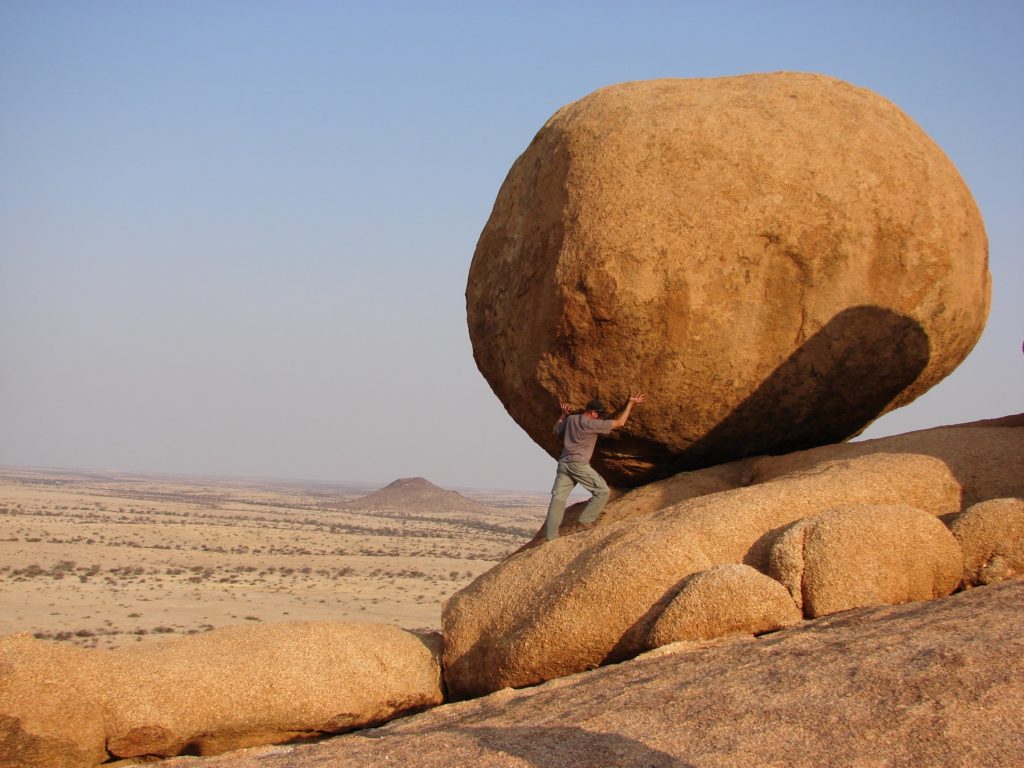

All of these understandings of resilience are legitimate, of course, depicting different facets of the inner-strength needed to persevere in this life. My take? I think of resilience as a person’s ability to recover from trauma or crisis. A resilient person understands that the storms of life arrive indiscriminately with varying levels of ferocity. One day you may be on the top of the mountain with the best view of the world imaginable, the next day you may be down in the deepest valley.

Regardless of the setting or situation, a resilient person musters the energy and urgency necessary to deal with the crisis, but then can return to a typical level of functioning quickly when the crisis is in rear view. A resilient person can work through the internalized storms, as well, in way that doesn’t jeopardize the wellbeing of others.

How to be a Resilient Father

Resiliency is a quality healthy fathers must have in the psycho-emotional toolbox. On the one hand, resilient fathers need to be equipped to manage their own issues in a way that keeps them in a strong position to support their partners and children. How is this sort of resiliency achieved? Personal management.

Father’s who engage in physical and emotional self-care develop the reserves of stamina, creativity, and problem-solving acumen they will draw from when the crisis arrives. A regular exercise routine, a hobby, a meditative practice, a willingness to learn, and connections with wise and supportive friends are vital for those who wish to bolster their resiliency.

In the aftermath of the crisis, resilient fathers reflect on events and issues, discerning what worked in the crisis and what did not. Obviously, this sort of reflection is most effective when trusted friends or teachers offer feedback. Thirteen years after my son’s diagnosis, I still surround myself with men and women who hold me accountable for my choices and indecision.

The Results of Resiliency

Resilient fathers model resilient behavior for their loved ones. In the midst of a crisis, steadiness and vision from a father will help the others in the family circle recognize their own ability to persevere when there is a challenge or trouble. Indeed, resilience is a component of leadership. If I continued my tirade and self-loathing for days and weeks after my son’s diagnosis, I would have nonverbally communicated to my family, “This situation is beyond all hope.”

In reality, we were surrounded by assets, that is, talented people who had the experience and training to help our son and family thrive beyond the chaos. While denial, anger, and bargaining are part of the grief process, the transition to acceptance of the loss or crisis is the beginning of a healthy response. Resilient fathers don’t perpetually decry the crisis, they muster resources and respond. The family system will respond too.

My son will be sixteen soon. He’s driving these days, loves talking college football, excels in athletics, and expects to enlist in the Air Force following his graduation from high school. He’s articulate, wise, strong as an ox, and among the most resilient people I know. I like to think I played a small role in his climb to wellness.

Friends, the crisis will come. What we do after the crisis is a function of our resilience.